Sometimes, even your native language can be a foreign language.

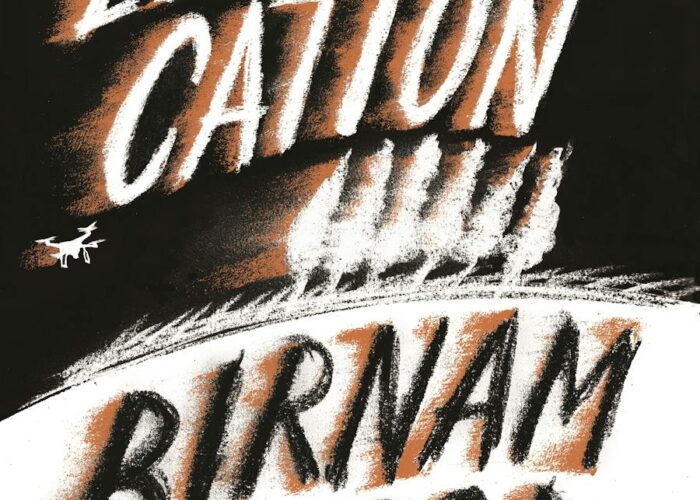

I recently read the novel Birnam Wood by Eleanor Catton, which is set in New Zealand. It’s a rare beast—a work of literary fiction that becomes increasingly suspenseful and intricately plotted as it develops. As you might expect, since the title is a reference to Macbeth, issues of power, ambition, and manipulation loom over the characters, even if at first they seem like quite ordinary people.

A New Zealand Setting

As for the language and culture, the novel feels firmly planted in New Zealand. And this was a key part of the reading experience. For one thing, the natural beauty of the setting plays such a major role in the book that it is essential to feel the presence of that land. One of the first linguistic differences I noticed was the phrase “leaving party.” In American English, we’d call it a “going-away party.” These multiple references to a “leaving party” were a nice reminder that I was reading about a different culture—a little like hearing a different accent when someone is speaking. I’m glad that no over-zealous editor decided to localize this term to “going-away party.”

Another unfamiliar term is “hui,” a Maori word for a community gathering or assembly. This is the kind of word that makes Merriam-Webster flatter you that “you must love words” when you search for it because it’s only in their unabridged dictionary. It’s clear enough from the context what it means. But it’s certainly a foreign word to most English speakers.

Dialogue and Accent

Catton has a keen ear for dialogue, and the way her characters speak struck me as completely believable and natural. At times, it was also interesting to consider my own kind of English through a different lens. At one point, the novel’s sole American character, a creepy tech billionaire named Robert Lemoine, makes a phone call with his number blocked and tries to pretend he’s someone else. His “flat American accent” instantly flags him as suspicious. Oh, yeah, that’s my accent, too, I remembered. I should be hearing everyone in this novel speaking with a New Zealand accent in my head!

Fiction in Translation

A similar kind of foreignness comes up with books in translation. And when translating books from other languages, we also need to let our English expand to admit other perspectives. Foreign words or different phrasing remind us that the book is taking us somewhere else, out of the typical context we’re used to. In translation, there are times we should let the foreign fabric come through, so the book can really be itself, and so we can maximize the reader’s experience.

Top image: Macmillan Publishers; middle image: Wikimedia Commons; bottom image: Wikimedia Commons