Seeing “City as Canvas” at the Museum of the City of New York, which opened yesterday and is up through August 24, was an unexpectedly rewarding, and even moving, experience. Not so much because of the quality of the art, some of which I was disappointed by, but because the show is so clearly a collaborative labor of love.

East Village artist and collector Martin Wong entrusted his collection of graffiti art to the museum while he was dying of AIDS. In the show, there is a video of DAZE (Chris Ellis), Sharp (Aaron Goodstone), and Lee Quiñones going through the artwork and reminiscing about those days and about Wong. There’s even footage of an emaciated Wong telling someone over the phone that “they’re here to move my collection” before the camera pans to his closets stuffed with art. There’s a raw pathos to the footage because of his illness, but I don’t think he was sad. There was a clear satisfaction in his voice at having found a home for his art, and at how many trucks it would take to transport it. This is a man who, according to DAZE, wanted to be the Albert Barnes of graffiti art. The only way to put it may come off as kind of hokey: these works are imbued with Martin Wong’s love.

When I visited the show, some male visitors in their 50s or early 60s who had been part of the graffiti scene in that era were sharing stories. It was not your regular museum crowd — there was a curiosity, an engagement, and a socio-economic diversity that you don’t usually feel at a museum show, and a sense that visitors were seeing their own world reflected back at them.

There’s a lot to learn here, too, about how the artists worked, putting together black books of sketches (Wong owned several) in which their friends would also jot down drawings and tags. There was an effort to get street art into galleries as of the early 80s, which was sooner than I realized, although the galleries were often short-lived (Wong’s own Museum of Graffiti Art only lasted six months) and the work didn’t attract much notice from the conventional art world (even if Sharp did have his work shown at Art Basel in the early 80s). You can also see the artists at work in the great photographs of Martha Cooper and Henry Chalfant, who were the first to document the New York City graffiti scene with their 1984 book “Subway Art.”

Martin Wong’s concern for the longevity of street artists’ work seems especially instructive in light of the demolition of 5 Pointz. During an era where graffiti was treated as a scourge, it could hardly be hoped that these works would stick around, even if Wong did have a fantasy that the city of New York would remove Lee’s “Howard the Duck” from a handball court at the artist’s junior high school and preserve it. Since that obviously wasn’t going to happen, he had Lee recreate the iconic piece ten years later on canvas. I would have loved to stumble upon it in real life, but it’s still pretty great to see it on canvas.

So how does a graffiti artist approach working on canvas? Do you treat it like a wall, or like something else? Some of the artists here try to do something else — you could almost call it graffiti history painting. They paint themselves doing or looking at graffiti. There are also East Village party scenes. I don’t think these works are that successful. They have a naïve, cartoonish quality, and are missing the energy, flair, and spontaneity of graffiti art. It seems to me that artists such as Crash, whose tag strains at the edges of the canvas and has the directness of Roy Lichtenstein, and Futura 2000, whose colorful lines shimmer with abstraction and movement in carefully-constructed compositions, have done something more powerful and original.

Most powerful of all are the photos and films of whole train cars alive with tags and images, traces of an era when street art was graffiti and graffiti was a crime. Let’s not get too nostalgic — this is an old model of subway car that looks pretty crappy — but, wow, there was something wild, and fun, and authentic going on.

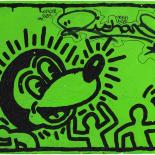

Image: Keith Haring, “Untitled.” Courtesy the Museum of the City of New York.